QT Prolongation Risk Assessment Tool

Patient Risk Assessment

This tool helps determine your patient's risk of QT prolongation when using antiemetic medications based on key clinical factors.

Risk Assessment Results

Antiemetic Safety Comparison

Compare QT prolongation risks of common antiemetics:

| Antiemetic | Max QTc Prolongation | IV Dose Limit | Cardiac Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ondansetron | 20 ms | 16 mg (max) | High |

| Dolasetron | 25-30 ms | Not recommended | Very High |

| Granisetron | 6-8 ms | 3 mg IV | Low |

| Palonosetron | 9.2 ms | 0.25 mg IV | Moderate |

| Droperidol | 15-20 ms | 2.5 mg IV | High |

| Prochlorperazine | 10-15 ms | 10 mg IV | Moderate |

Ondansetron is one of the most commonly used drugs to stop nausea and vomiting, especially in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or after surgery. But behind its effectiveness lies a quiet but serious danger: it can stretch the heart’s electrical cycle, leading to a potentially deadly rhythm problem called torsades de pointes. This isn’t theoretical. It’s documented. It’s warned about. And yet, many clinicians still give it in unsafe doses.

What QT Prolongation Really Means

The QT interval on an ECG measures how long it takes the heart’s ventricles to recharge after each beat. When this interval gets too long, the heart’s electrical system becomes unstable. That’s when torsades de pointes-a chaotic, fast rhythm-can kick in. It doesn’t always cause symptoms, but when it does, it can lead to fainting, seizures, or sudden death. The longer the QT, the higher the risk. And ondansetron is one of the top drugs linked to this effect.How Ondansetron Affects the Heart

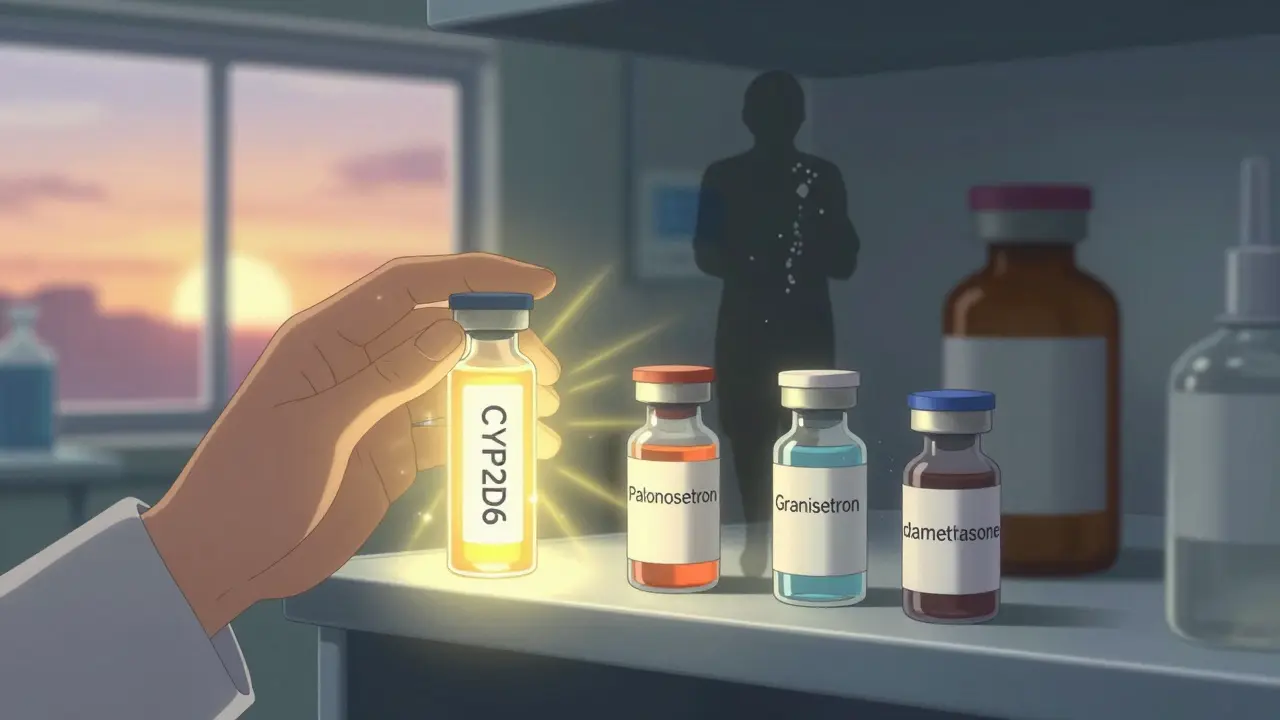

Ondansetron blocks serotonin receptors to calm nausea, but it also blocks a specific potassium channel in the heart called hERG. This channel helps the heart reset after each beat. When it’s blocked, the heart takes longer to recover, which shows up on an ECG as a longer QT interval. Studies show that a single 32 mg IV dose of ondansetron can lengthen the QTc (corrected QT) by up to 20 milliseconds. That’s not a small number. For context, a 10 ms increase in QTc is linked to a 5-7% higher risk of dangerous arrhythmias. The FDA stepped in back in 2012 after GlaxoSmithKline’s own study confirmed the danger. They said: stop giving 32 mg IV doses. Never exceed 16 mg in a single IV dose. Even that 16 mg dose carries risk if the patient has other problems-like low potassium, heart failure, or already a prolonged QT interval.Not All Antiemetics Are Equal

Ondansetron isn’t the only antiemetic that affects the heart, but it’s one of the most widely used-and the most dangerous in high doses. Here’s how the major ones compare:| Antiemetic | Class | Max QTc Prolongation (ms) | IV Dose Limit | Cardiac Risk Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ondansetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 20 | 16 mg single IV dose | High |

| Dolasetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 25-30 | Not recommended for IV use | Very High |

| Granisetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 6-8 | 3 mg IV | Low |

| Palonosetron | 5-HT3 antagonist | 9.2 | 0.25 mg IV | Moderate |

| Droperidol | Butyrophenone | 15-20 | 2.5 mg IV | High |

| Prochlorperazine | Phenothiazine | 10-15 | 10 mg IV | Moderate |

Granisetron and palonosetron are safer bets for patients with heart conditions. The American Society of Clinical Oncology now recommends palonosetron over ondansetron for patients with cardiac risk factors. Why? Because it has similar anti-nausea power but a much smaller effect on the heart.

Who’s at the Highest Risk?

It’s not just about the dose. The real danger spikes when multiple risk factors pile up:- Baseline QTc over 450 ms in men or 470 ms in women

- Low potassium (below 3.5 mEq/L) or low magnesium (below 1.8 mg/dL)

- Heart failure or bradycardia

- Older age-especially over 75

- Already taking other QT-prolonging drugs (like certain antibiotics, antidepressants, or antifungals)

- Genetic factors: poor metabolizers of CYP2D6 enzyme process ondansetron slower, leading to higher blood levels

A 2019 Johns Hopkins case series found that three out of 15 elderly patients with existing heart issues developed QTc intervals over 500 ms after an 8 mg IV dose-well into the danger zone. That’s not rare. It’s predictable.

What Clinicians Are Doing Differently Now

Since the FDA warning, things have changed-slowly, but they have changed.A 2020 survey of 256 anesthesiologists found that 78% changed their dosing habits. Most now use 4-8 mg IV instead of the old 16 mg standard. Hospitals are catching on too. 92% of U.S. hospitals now have formal protocols for monitoring ondansetron use in high-risk patients, up from just 37% in 2011.

Best practices now include:

- Check a baseline ECG if the patient has any cardiac risk factors

- Correct electrolytes before giving IV ondansetron-especially potassium and magnesium

- Limit IV dose to 8 mg in high-risk patients, not 16 mg

- Avoid 32 mg doses entirely-ever

- Monitor ECG for 4-6 hours after administration in vulnerable patients

At Massachusetts General Hospital, emergency medicine teams now use dexamethasone alone for low-risk nausea cases instead of ondansetron. Why? Because it works just as well for many patients and carries zero cardiac risk.

What About Oral Ondansetron?

Oral ondansetron is much safer. The FDA says single oral doses up to 24 mg (like for chemotherapy nausea) don’t require dose adjustments. Why? Because oral absorption is slower, and peak blood levels don’t spike like they do with IV push. But even oral use isn’t risk-free in people with multiple risk factors. If someone has a baseline QTc of 480 ms and is on multiple QT-prolonging drugs, even 8 mg orally could be dangerous.

Alternatives That Work

You don’t have to stick with ondansetron. There are safer, equally effective options:- Palonosetron: Lower QT risk, longer duration. Preferred for high-risk patients.

- Granisetron (especially transdermal): Minimal cardiac effect.

- Dexamethasone: Steroid with strong anti-nausea effects. Often used with other agents.

- Aprepitant/fosaprepitant: NK1 receptor antagonists. Great for delayed nausea, no QT effect.

- Metoclopramide: Use cautiously-it has its own cardiac risks, but less QT prolongation than ondansetron.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends combining dexamethasone with a 5-HT3 antagonist to reduce the total dose needed. That’s a smart strategy: get the benefit, cut the risk.

The Bigger Picture

Ondansetron is still the most prescribed antiemetic in the U.S.-18.7 million prescriptions in 2022. But IV use has dropped 22% since 2012. That’s because people are learning. The market for safer alternatives has grown 15.3% annually since the FDA warning. Palonosetron and aprepitant are now standard in many oncology centers.Research is moving toward personalized dosing. The NIH-funded QT-EMETIC trial, set to finish in mid-2024, is testing whether genetic testing for CYP2D6 metabolism can guide safer ondansetron use. If it works, we could soon be tailoring doses based on a patient’s DNA.

What You Need to Remember

- Don’t give 32 mg IV ondansetron. Ever. It’s banned for good reason. - Never exceed 16 mg IV in a single dose. Even that’s risky. - For high-risk patients, cap IV doses at 8 mg. - Always check electrolytes and baseline ECG if there’s any cardiac history. - Consider alternatives like palonosetron, granisetron, or dexamethasone. - Monitor ECG for at least 4 hours after IV administration in vulnerable patients.The goal isn’t to avoid ondansetron entirely. It’s a powerful drug. But it’s not a one-size-fits-all solution. The safest choice isn’t always the most familiar one.

Can ondansetron cause sudden death?

Yes, in rare cases. Ondansetron can trigger torsades de pointes, a dangerous heart rhythm that can lead to sudden cardiac arrest. This risk is highest with IV doses over 16 mg, especially in patients with preexisting heart conditions, low potassium, or genetic factors that slow drug metabolism. Between 2012 and 2022, the FDA recorded 142 cases of ondansetron-associated torsades, with 87% linked to doses exceeding 16 mg.

Is oral ondansetron safe for heart patients?

Oral ondansetron carries significantly lower risk than IV, but it’s not risk-free. Single oral doses up to 24 mg are considered safe by the FDA for most patients. However, if someone has a baseline QTc over 470 ms, heart failure, or is on other QT-prolonging drugs, even oral ondansetron could be dangerous. Always check ECG and electrolytes before use in high-risk patients.

Which antiemetic is safest for patients with long QT syndrome?

For patients with congenital or acquired long QT syndrome, palonosetron is the preferred 5-HT3 antagonist because it causes the least QT prolongation (max 9.2 ms vs. 20 ms for ondansetron). Dexamethasone and aprepitant are also excellent alternatives with no known QT effects. Avoid ondansetron, dolasetron, and droperidol entirely in these patients.

Should I check an ECG before giving ondansetron?

Yes-if the patient has any risk factors: age over 65, heart failure, history of arrhythmia, low potassium or magnesium, or is taking other QT-prolonging drugs. A baseline ECG helps determine if the QT interval is already prolonged. If it is, consider lowering the dose or switching to a safer antiemetic. Many hospitals now require pharmacist review of QTc before high-dose IV ondansetron.

How long does ondansetron affect the QT interval?

The peak effect occurs about 3 minutes after IV administration and can last up to 120 minutes. That’s why monitoring for at least 4-6 hours is recommended in high-risk patients. Even after the drug leaves the bloodstream, the heart’s electrical system may remain unstable for hours. Don’t assume the risk is over once the nausea is gone.

What’s the difference between QT and QTc?

QT is the raw measurement of the heart’s repolarization time. QTc is the corrected version, adjusted for heart rate. A fast heart rate shortens the QT interval, and a slow heart rate lengthens it. QTc removes that variability so you can compare values across different heart rates. Clinicians use QTc (usually corrected by Bazett’s or Fridericia formula) to assess risk. Normal QTc is under 450 ms in men and 470 ms in women.

12 Comments

December 20, 2025 Nancy Kou

Finally, someone laid this out clearly. I’ve seen too many residents push 16 mg IV ondansetron like it’s candy. This isn’t just about protocol-it’s about survival. The data doesn’t lie, and neither do the ECGs.

December 21, 2025 Hussien SLeiman

Let’s be real-this whole thing is a classic case of pharmaceutical inertia. Ondansetron’s cheap, it’s branded, and everyone’s used to it. But when you’ve got a 20ms QTc spike on a patient already on amiodarone and with a potassium of 3.2, you’re not being proactive-you’re playing Russian roulette with a loaded gun. And don’t even get me started on how hospitals still don’t have automated QTc alerts in their EMRs. It’s 2024. We have AI that can predict stock prices. Why can’t it flag a 480ms QTc before you hit ‘administer’?

December 22, 2025 William Liu

Great breakdown. I’ve switched my whole oncology unit to palonosetron for high-risk patients and the drop in arrhythmia alerts has been night and day. Also, dexamethasone alone works better than people think for mild nausea. Less drug, less risk. Win-win.

December 22, 2025 Danielle Stewart

As a nurse who’s had to rush to code a patient after a routine 16mg IV ondansetron, I can’t stress this enough: check the ECG. Check the K+. Check the meds. Don’t assume they’re ‘fine.’ That one time we skipped the baseline because the patient was ‘just getting post-op nausea’? We lost 12 minutes before we realized what was happening. Don’t be that team.

December 23, 2025 mary lizardo

While the clinical observations presented are empirically valid, the rhetorical framing exhibits a concerning degree of alarmism. The incidence of torsades de pointes remains exceedingly rare, even among high-risk cohorts. The disproportionate emphasis on ondansetron-while neglecting the confounding influence of polypharmacy, baseline electrolyte derangements, and underlying cardiac pathology-risks fostering therapeutic nihilism. Evidence-based medicine requires nuance, not fear-driven dogma.

December 23, 2025 Isabel Rábago

People act like this is new news. I’ve been telling residents for years that 32 mg is a death sentence waiting to happen. And yet, every month, someone still tries to justify it because ‘the patient was really nauseated.’ No. Just no. You don’t cure nausea at the cost of a heartbeat. If you’re that desperate, give them a Zofran suppository or just let them rest. Their body will catch up.

December 25, 2025 Monte Pareek

Look I’ve worked ER in three states and let me tell you this-most docs don’t even know what QTc stands for. They see ‘anti-nausea’ and they grab the bottle. The fact that 92% of hospitals now have protocols? That’s progress. But the real win is when the pharmacist stops the order and says ‘hold up, this patient’s on ciprofloxacin and has a QTc of 490.’ That’s the hero we need more of. Also-palonosetron costs more? So what? A code blue costs more. A funeral costs more. We’re not saving pennies here, we’re saving lives.

December 25, 2025 Mark Able

So you’re telling me we’re not supposed to use the most effective drug for chemo nausea? What’s next, no morphine because it can cause respiratory depression? This is just another example of medicine becoming more about liability than patient care. If you’re scared of QT prolongation, then monitor the patient. Don’t punish everyone because a few people were careless.

December 27, 2025 Kevin Motta Top

Granisetron transdermal patch is underrated. No IV. No spikes. Lasts 3 days. Works great for outpatient chemo. I’ve used it on 30+ elderly patients with no issues. No ECG needed. No electrolyte checks. Just slap it on and walk away. Why aren’t we pushing this more?

December 29, 2025 Marsha Jentzsch

Wait… so you’re saying the FDA didn’t ban ondansetron because the drug companies paid them off? And now they’re pushing expensive alternatives? And the NIH is testing genetic testing to see who dies? This is all a scam. They want you to buy palonosetron. They want you to pay for ECGs. They want you to be scared. I’ve given ondansetron for 15 years. My grandma took it. She’s fine. You’re all overreacting. It’s just nausea.

December 29, 2025 Janelle Moore

Did you know the real reason they’re pushing palonosetron is because the government is secretly testing if blocking serotonin can make people less angry? That’s why they changed the dose limits. It’s not about the heart-it’s about controlling the population. They don’t want you feeling better. They want you docile.

December 29, 2025 mary lizardo

Your assertion that the FDA’s actions are motivated by profit is both unsupported and factually incorrect. The agency’s 2012 warning was based on peer-reviewed pharmacokinetic data and post-marketing surveillance reports submitted by GlaxoSmithKline themselves. To suggest this is a coordinated conspiracy is not only absurd, it undermines the integrity of clinical practice. If you are genuinely concerned about patient safety, direct your energy toward advocating for mandatory ECG monitoring protocols-not baseless paranoia.

Write a comment