Metformin Contrast Dye Decision Tool

Metformin & Contrast Dye Decision Tool

This tool follows current guidelines (2023) to help determine if you should stop metformin before imaging procedures using contrast dye. Based on your eGFR and other risk factors, it provides evidence-based recommendations.

Over 150 million metformin prescriptions are filled in the U.S. each year. But when it's time for a CT scan or angiogram, many patients ask: metformin contrast dye interactions-should you stop taking it? For decades, doctors told patients to hold metformin for days before and after imaging tests. New evidence shows that’s often unnecessary. Let’s cut through the confusion.

Why the Confusion? Historical vs Current Guidelines

Before 2016, the FDA required patients to stop metformin before any procedure using contrast dye. You’d typically hold it 48 hours before and after the test. This rule applied to everyone, no matter their kidney function. The fear was simple: contrast dye might harm kidneys, causing metformin to build up and trigger lactic acidosis-a dangerous drop in blood pH.

But here’s the truth. Studies now show the actual risk is extremely low. According to FDA data, fewer than 10 cases of metformin-associated lactic acidosis happen per 100,000 patient-years of exposure. Most cases involve patients with severe kidney problems or other health issues. The old guidelines were based on theoretical risks, not real-world evidence.

Understanding Lactic Acidosis: The Real Risk

Lactic acidosis happens when lactate builds up in your blood faster than your body can clear it. Symptoms start subtly: nausea, abdominal pain, or unusual tiredness. As it worsens, you might experience vomiting, rapid breathing, or confusion. In severe cases, it can lead to organ failure.

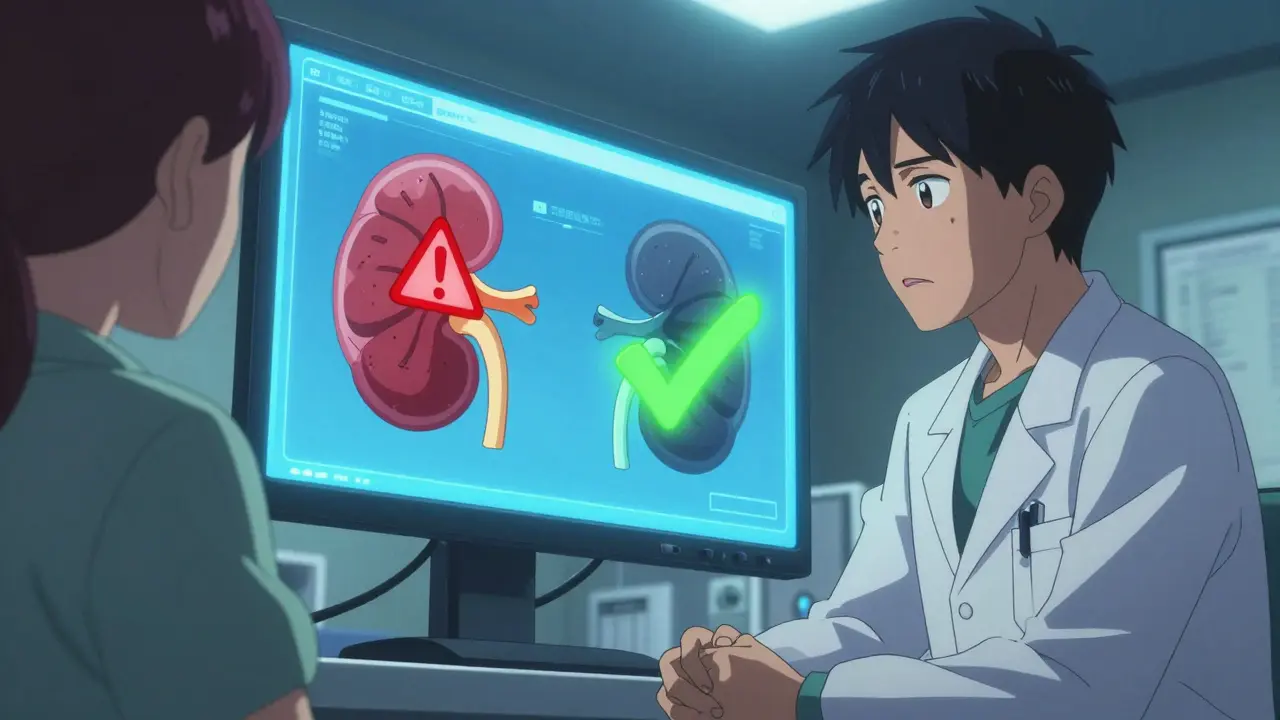

Metformin itself doesn’t cause lactic acidosis in healthy kidneys. It works by slowing glucose production in the liver and improving insulin sensitivity. The problem arises only when kidneys can’t clear metformin properly. With normal kidney function (eGFR >60), metformin is eliminated safely. But if your kidneys are impaired (eGFR <60), metformin can accumulate. Add contrast dye, which might temporarily reduce kidney function, and the risk increases. However, even then, the risk remains very low for most people.

Current Guidelines Based on Kidney Function

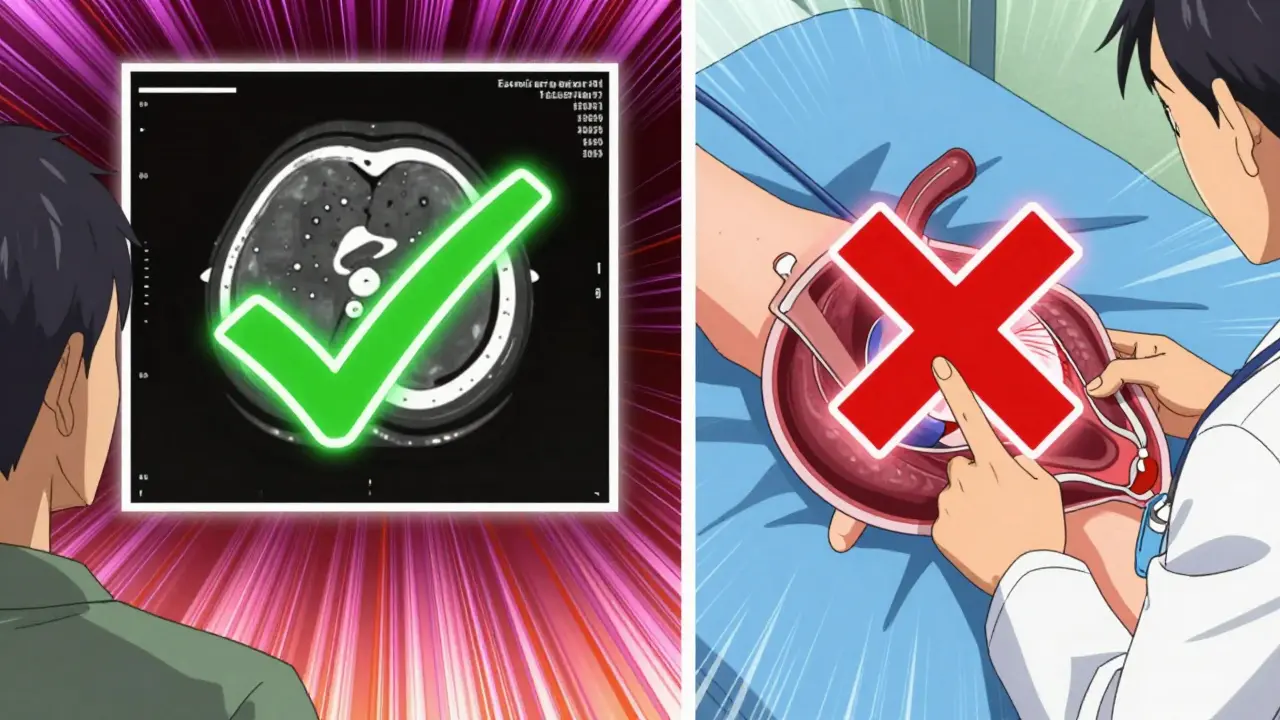

Today, guidelines focus on your kidney health. The American College of Radiology (ACR) and National Kidney Foundation (NKF) agree: no need to stop metformin if your eGFR is above 60. For patients with eGFR between 30 and 60, hold metformin before the procedure and restart only after 48 hours if kidney function stays stable. But if you’re getting intraarterial contrast-like during a cardiac catheterization-you must stop metformin regardless of kidney numbers.

| Contrast Type | eGFR >60 | eGFR 30-60 | Other Risk Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intravenous (IV) | Continue metformin | Hold before procedure; restart after 48h if stable | Hepatic impairment, heart failure, alcoholism |

| Intraarterial (IA) | Hold metformin | Hold metformin | All cases require holding regardless of eGFR |

Why the difference between IV and IA contrast? Intraarterial procedures (like heart catheterizations) use higher contrast doses directly in arteries. This can cause more significant kidney stress. Intravenous contrast (like for CT scans) is safer for kidneys in most cases. Always check with your doctor about your specific procedure type.

Practical Steps for Patients and Doctors

If you’re on metformin and need imaging:

- Check your eGFR before the procedure. This blood test measures kidney function. Ask your doctor for the number-it’s more useful than just "kidneys are okay."

- Don’t stop metformin without advice. Missing doses can spike blood sugar. Only pause it if your doctor confirms it’s needed.

- Know your contrast type. A routine chest CT uses IV contrast; a heart catheterization uses IA. This changes your protocol.

- Monitor symptoms after the test. If you feel unwell, seek help immediately. Lactic acidosis is rare, but early treatment saves lives.

For doctors: Recheck eGFR 48 hours after the procedure before restarting metformin. If your patient has other risks-like liver disease, heart failure, or severe infection-tailor the plan. Always prioritize individualized care over blanket rules.

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I stop metformin before a standard CT scan?

Only if your eGFR is below 60. For most people with healthy kidneys (eGFR >60), you can keep taking metformin. If your eGFR is between 30-60, hold it for 48 hours before and after the scan. Always confirm with your doctor first.

What if I need a cardiac catheterization?

Yes, stop metformin. Cardiac catheterizations use intraarterial contrast, which carries higher risk. Hold the medication before the procedure and restart only after 48 hours, once kidney function is stable. Your doctor will guide you on timing.

Can contrast dye permanently damage my kidneys?

Contrast-induced kidney injury is usually temporary. Most people’s kidneys recover within 48 hours. The risk is higher if you already have kidney disease, diabetes, or dehydration. Drinking plenty of water before and after the scan helps protect your kidneys. Always discuss your risks with your healthcare team.

How do I know my eGFR is safe?

Your eGFR number is in your blood test results. Above 60 is generally safe for continuing metformin. Between 30-60 means you may need to pause it temporarily. Below 30 requires careful planning-your doctor might recommend alternatives to contrast dye or adjust your diabetes treatment. Always review results with your healthcare provider.

Is lactic acidosis common with metformin?

Extremely rare. Studies show 1-9 cases per 100,000 people taking metformin. Most cases happen in people with severe kidney failure, liver disease, or other serious health issues. When caught early, treatment with IV fluids and dialysis usually reverses it. Don’t let fear of this rare event stop you from necessary imaging tests.

10 Comments

February 6, 2026 jan civil

Always check eGFR before procedure.

February 7, 2026 Lisa Scott

FDA and pharma companies are hiding the risks they say it's safe but it's not always stop metformin no exceptions trust me I know

February 9, 2026 Kieran Griffiths

Patients should know their eGFR before procedures. Discuss with doctor. No panic needed.

February 9, 2026 Jenna Elliott

US doctors know best Foreign guidelines are wrong always stop metformin trust the system

February 10, 2026 Gregory Rodriguez

Wow nothing says I care about your kidneys like vague guidelines Lets just wing it and hope for the best #Sarcasm

February 11, 2026 Tehya Wilson

Guidelines updated eGFR essential confirm with healthcare provider do not self diagnose

February 12, 2026 Johanna Pan

In the US we often overlook kidney health But in my culture we check egfr first Its crucial Always ask doc for numbers 😊

February 13, 2026 Elliot Alejo

I've seen many patients with eGFR >60 continue metformin safely Its all about individual assessment No blanket rules

February 14, 2026 one hamzah

Hey everyone! 😊 Metformin is a lifesaver for many but when it comes to contrast dye egfr is key.

If kidneys good (egfr >60) no need to stop.

If not hold it.

Always consult doc. 🙌 #StaySafe.

In India we have many patients on metformin guidelines similar.

We check creatinine before procedures.

Better safe than sorry.

Stopping metformin can cause high blood sugar dangerous.

Balance is key.

Doctors assess individually.

Egfr 30-60 hold for 48h.

Above 60 safe continue.

Contrast type matters IV vs IA.

IV safer for kidneys.

IA procedures like heart cath riskier.

Check with healthcare provider.

They know best.

Don't let fear stop necessary tests.

Key is kidney function check.

Spread this knowledge. 😊

February 15, 2026 Kate Gile

Great point! Always check kidney function before procedures. It's the safest approach. Let's spread this knowledge!

Write a comment