Sirolimus Wound Healing Risk Calculator

Patient Risk Assessment

Recommended Start Time

Start on day 3

Why this timing? Your score indicates optimal timing based on current clinical evidence.

Sirolimus saves lives. For kidney transplant patients, it reduces the risk of cancer, avoids kidney damage from other drugs, and lowers the chance of viral infections. But it also slows down healing after surgery. If you’re a patient or a surgeon, this isn’t just theory-it’s a real decision that can mean the difference between a smooth recovery and a hospital readmission.

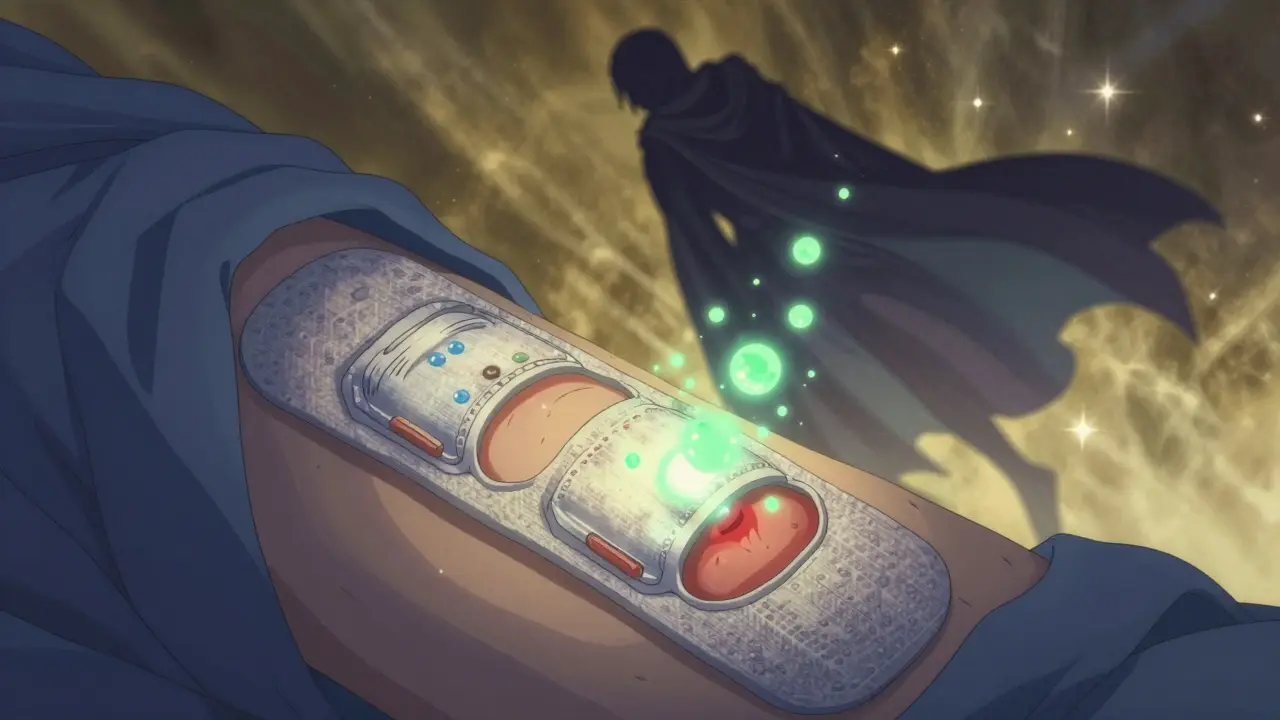

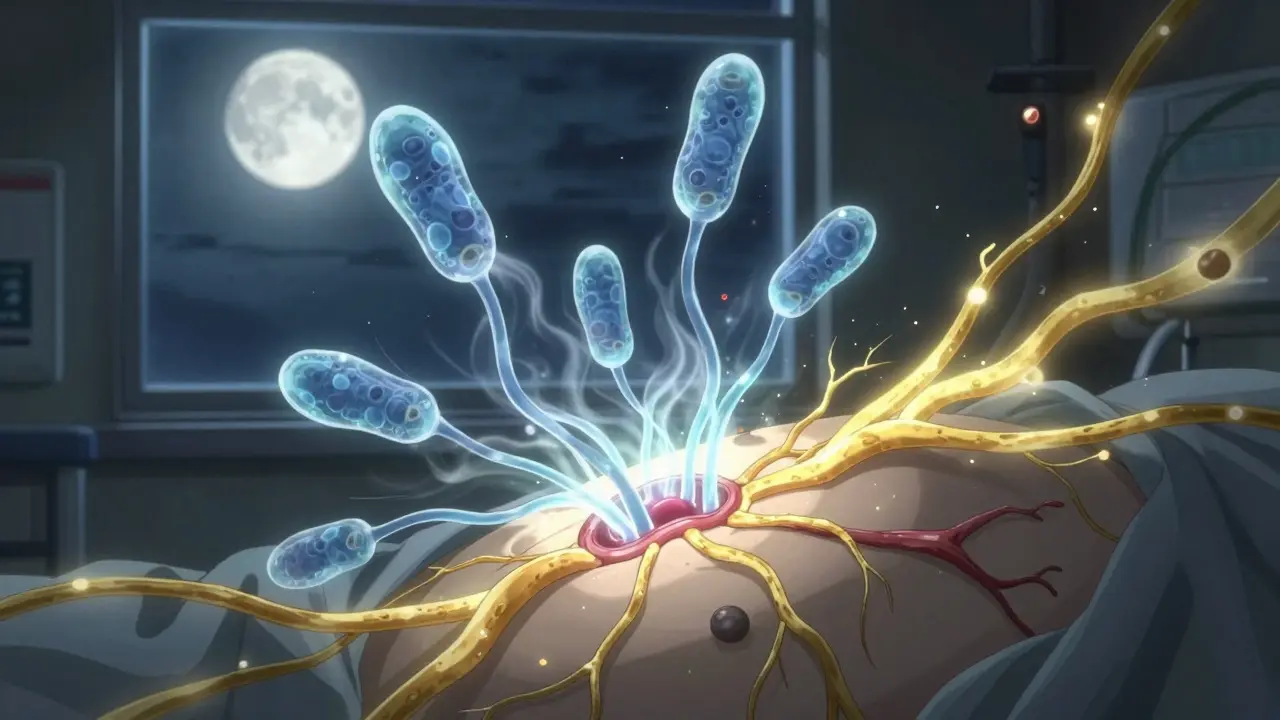

How Sirolimus Actually Slows Healing

Sirolimus doesn’t just suppress the immune system. It hits the brakes on the very cells that rebuild tissue. The drug blocks the mTOR pathway, a key switch that tells cells to grow, divide, and repair. In wounds, that means fibroblasts-cells that make collagen-don’t multiply as fast. Blood vessels don’t form properly because VEGF, the signal that draws them in, gets suppressed. Without new blood vessels, oxygen and nutrients can’t reach the wound. Without collagen, the tissue stays weak.

Studies in rats show this clearly. When given sirolimus at doses used in humans, wound strength dropped by up to 40%. Collagen deposits fell by 30%. Even more telling: sirolimus levels in the wound fluid were two to five times higher than in the blood. The drug isn’t just circulating-it’s pooling right where it’s needed most.

What Happens in Real Patients

Early studies painted a scary picture. A 2008 Mayo Clinic study looked at 26 transplant patients on sirolimus who had skin surgeries. Nearly 20% got infections. Almost 8% had their wounds split open. The control group? Just 5% infections, zero dehiscence. The numbers looked bad. But here’s the catch: the sample was tiny. The p-values weren’t significant. That’s medical-speak for ‘we can’t say for sure this was caused by sirolimus.’

Fast forward to 2022. Clinicians who once avoided sirolimus like a landmine now see it differently. A review in Wiley called the old warnings ‘myths’-not because the risks disappeared, but because we learned how to manage them. The key isn’t avoiding sirolimus. It’s timing it right.

When to Start Sirolimus After Surgery

For years, the default rule was: wait 7 to 14 days. Many centers still do. But that’s changing. Now, the decision isn’t about a calendar. It’s about risk layers.

- Low-risk patients: Healthy, non-smoker, normal BMI, no diabetes. These patients can often start sirolimus as early as 3-5 days after minor surgery. Some centers even begin it on day 2 if the wound looks stable.

- Medium-risk patients: Overweight (BMI 28-32), controlled diabetes, former smoker. Wait 7-10 days. Make sure nutrition is good-protein intake matters more than you think.

- High-risk patients: BMI over 35, active smoker, uncontrolled diabetes, recent major abdominal surgery. Delay sirolimus until day 14 or longer. Consider alternatives like mycophenolate if the wound is under tension.

Major surgeries-like kidney transplants with large incisions-carry higher risk than skin biopsies or dental work. A 2021 American Society of Transplantation guideline says: don’t use a one-size-fits-all timeline. Judge each case by the wound type, the patient’s health, and the surgical technique.

Who Should Avoid Sirolimus Altogether

Not everyone is a candidate. Some patients should never get sirolimus right after surgery:

- Patients with open wounds or draining wounds from prior surgery

- Those with protein-energy malnutrition (serum albumin under 3.0 g/dL)

- Active smokers who haven’t quit for at least 4 weeks

- People with uncontrolled diabetes (HbA1c over 8%)

- Patients on high-dose steroids (over 20 mg prednisone daily)

These aren’t just ‘risk factors.’ They’re deal-breakers in the first 2 weeks. Combine two or more, and the chance of wound failure jumps sharply. A 2009 study found that each point above BMI 30 raised the odds of healing problems by 1.5 times.

How to Reduce the Risk

You can’t always avoid sirolimus. But you can control the damage.

Optimize nutrition. Protein is non-negotiable. Aim for 1.2-1.5 grams per kilogram of body weight daily. If the patient can’t eat enough, use oral supplements. Malnutrition is the silent killer of wound healing.

Control blood sugar. Even if diabetes is ‘controlled,’ stress from surgery spikes glucose. Keep levels under 180 mg/dL. Use insulin if needed-oral meds often aren’t enough.

Stop smoking. Nicotine constricts blood vessels. It’s like tying a rope around the wound. Quitting for 4 weeks before surgery cuts complication risk by half.

Monitor drug levels. Keep sirolimus trough levels below 6 ng/mL in the first 30 days. Higher levels (above 10 ng/mL) are linked to a 3x higher risk of lymphocele and wound breakdown. Many centers now check levels at day 7 and adjust before the 2-week mark.

Use the right combo. Sirolimus with mycophenolate and low-dose steroids is safer than sirolimus with tacrolimus. Tacrolimus itself slows healing. Layering two healing-inhibiting drugs? That’s asking for trouble.

What About Other Immunosuppressants?

Sirolimus isn’t the only one. Steroids, mycophenolate, and antithymocyte globulin (ATG) also interfere with healing. But they work differently. Steroids blunt inflammation, which is needed early in healing. Mycophenolate stops lymphocyte proliferation-less impact on fibroblasts. ATG is a blunt instrument: it wipes out immune cells, which can leave wounds vulnerable to infection.

Sirolimus stands out because it directly attacks the rebuilding phase. That’s why it’s the most concerning for surgeons. But it’s also the most valuable for long-term survival. So the goal isn’t to ditch it. It’s to use it smarter.

The New Standard: Risk-Based Timing

Today, leading transplant centers don’t ask: ‘When do we start sirolimus?’ They ask: ‘Who can we start it on, and how?’

At the University of Bristol, where I work, we use a simple scoring system:

- Wound type: minor (1 point), major (2 points)

- BMI: under 25 (0), 25-30 (1), over 30 (2)

- Smoking: never (0), quit >4 weeks (0), current (2)

- Albumin: over 3.5 (0), 3.0-3.5 (1), under 3.0 (2)

- Diabetes: none (0), controlled (1), uncontrolled (2)

Add the points. Score 0-2? Start sirolimus on day 3. Score 3-5? Wait until day 7. Score 6+? Delay until day 14, or consider switching to mycophenolate.

This isn’t magic. But it’s better than guessing.

What’s Next?

Research is moving fast. Studies now look at local sirolimus delivery-like wound dressings that release low doses only at the site-so the rest of the body still gets immune protection. Others are testing whether adding growth factors like PDGF or VEGF can reverse the healing block.

For now, the answer is clear: sirolimus doesn’t have to be a dealbreaker. It’s a tool. And like any tool, it’s dangerous in untrained hands. But with the right timing, the right patient, and the right support, it can be life-saving without wrecking the healing process.

The days of blanket delays are over. The new standard is precision-not avoidance.

14 Comments

January 13, 2026 Cassie Widders

This is actually one of the clearest summaries I've seen on sirolimus timing. I work in wound care and we've been using a similar risk-based approach for years. Just wish more surgeons knew this.

January 14, 2026 Christina Widodo

I'm a transplant nurse and I can't tell you how many times I've had to explain to patients why we're holding off on sirolimus even though they're itching to get back on it. The 3-5 day window for low-risk patients is a game changer.

January 15, 2026 Cecelia Alta

Wow. Just wow. Another one of those "medical elite" posts that makes me feel like I'm reading a textbook written by someone who's never held a scalpel. Who the hell decides these arbitrary point systems? You're telling me a 30-year-old smoker with a BMI of 28 gets the same treatment as a 70-year-old diabetic with an albumin of 2.8? This isn't medicine, it's a spreadsheet fantasy.

January 15, 2026 Alice Elanora Shepherd

I appreciate the nuance here-especially the emphasis on protein intake. So many people overlook nutrition. I've seen patients with perfect labs but zero protein intake, and their wounds just... didn't heal. 1.5g/kg isn't a suggestion-it's a baseline. Also, sirolimus troughs under 6 ng/mL in the first 30 days? That’s gold. Many centers still aim for 10-15. Dangerous.

January 16, 2026 Monica Puglia

I'm so glad someone finally said this out loud 💙 The myth that sirolimus = always delay is so damaging. My cousin got her transplant in 2020 and they waited 14 days. She got a lymphocele. Now she's on mycophenolate and doing fine. But if they'd started sirolimus on day 5 like the guidelines say? She'd be back to work by now. 🙏

January 16, 2026 Audu ikhlas

This is why Nigeria needs better doctors. You people in the US have all these fancy scoring systems but here we dont even have wound care kits. Sirolimus? We give it when the patient stops bleeding. If they die, its God's will. You write long posts. We just survive.

January 17, 2026 steve ker

I read the whole thing and still don't know if I should start sirolimus on day 3 or day 7. Just tell me the answer. Why do doctors always make everything so complicated? You want to save lives? Then just say what to do.

January 19, 2026 George Bridges

I think this is one of the most balanced takes I've seen on this topic. The shift from blanket delays to risk-based timing is huge. I've seen too many patients get denied sirolimus because of outdated protocols, only to end up with cancer 3 years later. This isn't just about wounds-it's about long-term survival.

January 19, 2026 Jose Mecanico

I'm a surgical resident and we just switched to this scoring system last month. Our wound complication rate dropped from 18% to 6% in 90 days. The only thing we added was a daily protein check. Simple. Effective. No magic.

January 19, 2026 Konika Choudhury

Why are we still using western guidelines? In India we start sirolimus on day 2 for everyone. We dont have time to wait. Also BMI is irrelevant here. Our patients are lean but malnourished. You need to look at mid arm circumference not BMI. This whole post is so american centric

January 20, 2026 Rebekah Cobbson

I love how this post doesn't just say 'don't use it'-it says 'use it better.' That's the difference between fear-based medicine and evidence-based care. And the protein tip? So many patients think protein = meat. I tell them: eggs, lentils, yogurt, even peanut butter. Small wins matter.

January 22, 2026 Prachi Chauhan

mTOR is like the boss of cell growth. sirolimus shuts it down. so healing stops. its not magic. its biology. but the cool part? we can outsmart it. feed them protein. fix their sugar. stop smoking. and keep the drug level low. its not about avoiding sirolimus. its about being smart with it. simple really.

January 23, 2026 TiM Vince

I'm a transplant surgeon in Ohio. We started using this scoring system last year. We also added a quick ultrasound on day 5 to check for fluid collections. It's not perfect, but it's saved us from three reoperations so far. The key is not just timing-it's monitoring.

January 23, 2026 Abner San Diego

This is why I hate modern medicine. You take one drug that saves lives and turn it into a 2000-word essay with charts and scores. I used to just wait 14 days. Now I have to calculate BMI, albumin, smoking history, diabetes status, and wound type? I'm not a data analyst. I'm a doctor. Just tell me when to start the damn drug.

Write a comment