Primary sclerosing cholangitis is not just another liver problem. It’s a slow, silent killer that eats away at the bile ducts inside and outside the liver, turning them into scar tissue over years-sometimes decades-before symptoms even show up. Unlike fatty liver or hepatitis, PSC doesn’t come from drinking too much or being overweight. It’s an autoimmune condition, meaning your own immune system attacks the bile ducts, and no one knows exactly why. By the time most people are diagnosed, the damage is already done. And there’s no pill to fix it.

What Happens When Bile Ducts Scar?

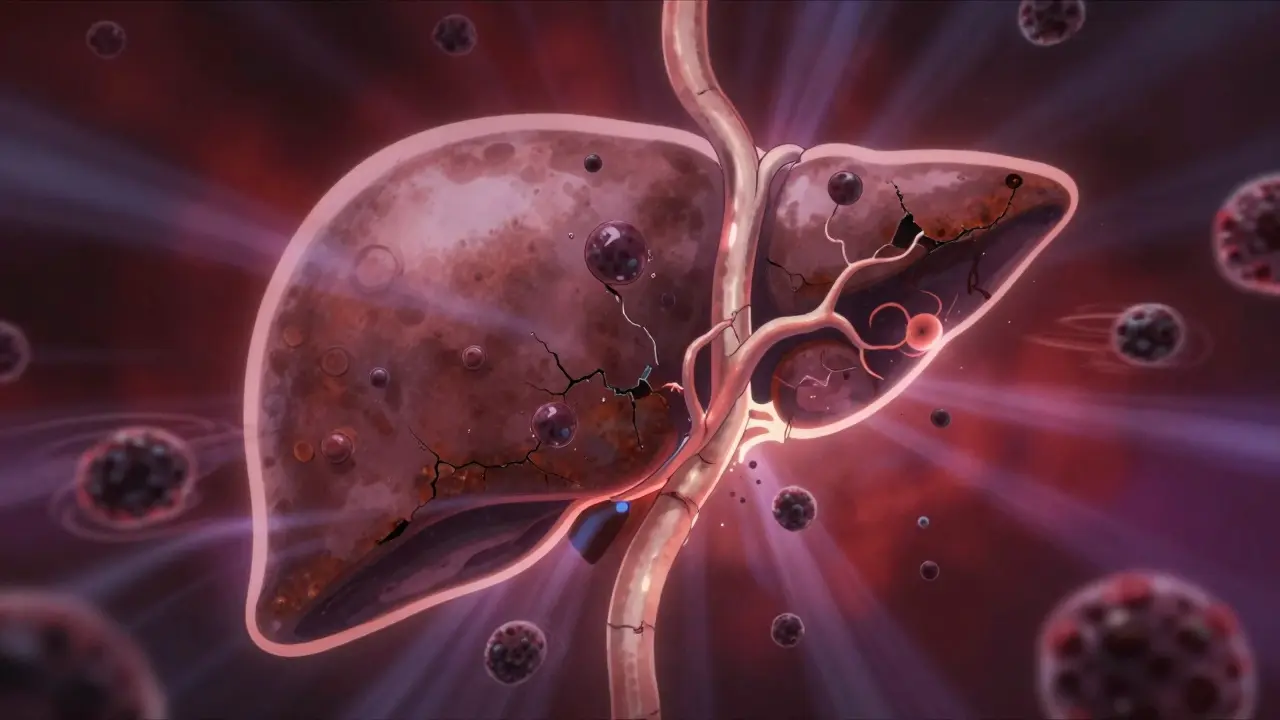

Your liver makes bile to help digest fat. That bile travels through tiny tubes called bile ducts to your small intestine. In primary sclerosing cholangitis, those ducts become inflamed, then stiff, then blocked. Imagine a garden hose that slowly gets clogged with rust and gunk. At first, water still flows. Then it trickles. Then it stops. That’s what happens in PSC. The bile backs up, poisoning the liver cells. Over time, this leads to cirrhosis-scarring so severe the liver can’t work anymore.

What makes PSC different from other liver diseases? It doesn’t just hit small ducts like PBC (Primary Biliary Cholangitis). It hits the big ones too-the ones you can see on an MRI scan. And it doesn’t show up on standard blood tests for autoimmunity. Only 20-50% of PSC patients test positive for p-ANCA, a marker doctors often look for. That’s why it’s so easy to miss. Many people wait years before getting a real diagnosis.

Who Gets Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis?

PSC is rare. About 1 in 100,000 people have it. But in places like Sweden, the rate is higher-6.3 per 100,000. Most people are diagnosed between 30 and 50, with the average age being 40. Men are twice as likely to get it as women. And if you have ulcerative colitis, your risk jumps dramatically. Up to 80% of PSC patients also have this form of inflammatory bowel disease. That’s not a coincidence. Researchers now believe the gut and liver are connected in a way that triggers this disease. A leaky gut lets bacteria and their waste products into the bloodstream, which then attack the bile ducts in people with the right genetic setup.

The strongest genetic link is the HLA-B*08:01 gene. People with this variant are over twice as likely to develop PSC. But genes alone don’t cause it. Something in the environment-maybe a virus, an antibiotic, or even diet-flips the switch. That’s why identical twins don’t always both get PSC, even if they share the same DNA.

What Are the Real Symptoms?

Most people with PSC feel fine for years. No pain. No jaundice. No obvious signs. That’s why it’s called a silent disease. When symptoms finally appear, they’re vague and easily ignored:

- Extreme fatigue-like your body’s been drained of all energy

- Itchy skin that doesn’t go away, even after antihistamines

- Right-sided abdominal discomfort

- Yellowing of the eyes or skin (jaundice)

- Dark urine, pale stools

One patient on Reddit described the itching as "coming from inside my bones." That’s not exaggeration. The bile acids build up in the skin and nerves, triggering a deep, unrelenting itch that keeps people awake at night. Many try everything: antihistamines, steroids, even cold showers. Only a few drugs work reliably-rifampicin, naltrexone, or colesevelam. But even those don’t help everyone.

How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no blood test for PSC. No single marker. Diagnosis comes from imaging. The gold standard is MRCP-magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. It’s like an MRI of your bile ducts. In PSC, the ducts look like a tree with broken branches-narrowed, irregular, blocked. Sometimes doctors use ERCP, a more invasive procedure that lets them see and even open up blocked ducts. But ERCP carries risks, so it’s usually saved for when treatment is needed.

Doctors also check liver enzymes. ALP (alkaline phosphatase) is almost always high in PSC. But here’s the catch: ALP can be elevated in other conditions too. That’s why imaging is non-negotiable. If your ALP is up and your MRI shows strictures, you’re likely dealing with PSC.

And if you have ulcerative colitis? You should be screened every 2-3 years, even if you feel fine. PSC often shows up before the bowel disease gets serious.

Why Is Ursodeoxycholic Acid (UDCA) No Longer Recommended?

For years, doctors gave patients high doses of UDCA, thinking it would flush out bile and protect the liver. It made sense. But multiple large studies showed it didn’t improve survival. Worse-doses above 28 mg per kg per day actually increased the risk of complications, including liver failure and death.

Today, both the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) say: Don’t use UDCA routinely. It’s not a treatment. It’s a placebo with side effects. Some doctors still prescribe it out of habit, but guidelines changed in 2023. If you’re still on high-dose UDCA, talk to your hepatologist. There’s nothing to gain-and real risks.

What About New Treatments?

For the first time in decades, there’s real hope. Several drugs are in late-stage trials:

- Obeticholic acid (OCA): A bile acid receptor activator. In a 2023 trial, it lowered liver enzymes by 32% in PSC patients taking 10 mg daily. But it caused bad itching in many, and the FDA hasn’t approved it yet.

- Cilofexor: A non-steroidal FXR agonist. Phase 2 results showed a 41% drop in ALP levels. The EMA gave it orphan drug status in early 2023.

- NorUDCA: A modified version of UDCA. Early data suggests it may reduce bile duct damage without the side effects.

These drugs don’t cure PSC. But they might slow it down. If they work, they could delay liver failure by years-or even prevent it in some cases. The PSC Partners Seeking a Cure registry, with over 3,100 patients across 12 countries, is helping researchers track who responds best to what.

The Big Fear: Cholangiocarcinoma

Every year, 1.5% of PSC patients develop bile duct cancer-cholangiocarcinoma. That’s 15 times higher than the general population. And once it happens, survival drops to just 10-30% at five years. That’s why surveillance is critical.

Doctors recommend annual MRI scans with contrast and blood tests for CA19-9, a tumor marker. But CA19-9 isn’t perfect-it can be high in PSC even without cancer. That’s why imaging is key. If a new mass shows up, you need urgent evaluation.

Some centers now use advanced MRI techniques like diffusion-weighted imaging to catch tumors earlier. But access is uneven. In rural Europe, only 35% of patients can get this level of monitoring. In major U.S. academic centers, it’s standard.

When Is a Liver Transplant Needed?

Transplant is the only cure. And it works. Over 80% of PSC patients survive five years after transplant. Many live 20+ years with a new liver. But it’s not simple. You have to be sick enough to qualify-but not so sick you won’t survive surgery. Most transplant centers use the MELD score (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) to decide who gets priority.

Here’s the hard truth: PSC patients often wait longer than those with other liver diseases. Why? Because their symptoms don’t always match their liver damage. Someone with high ALP and low albumin might be fine, while someone with mild lab values might be on the brink of failure. That’s why experienced centers look at more than just numbers-they watch how patients feel, how their bile ducts are changing, and whether cancer is developing.

After transplant, PSC can come back-in about 20% of cases. But it usually progresses slowly. Most patients never need a second transplant.

Living With PSC: What You Need to Know

Managing PSC isn’t just about meds. It’s about daily habits:

- Vitamins: Fat-soluble vitamins A, D, E, and K are poorly absorbed. Get them checked every 3-4 months. Many patients need high-dose supplements.

- Colon cancer screening: If you have ulcerative colitis, get a colonoscopy every 1-2 years. PSC raises your risk of colorectal cancer to 10-15% over your lifetime.

- Watch for infection: Fever, chills, and right-side pain could mean cholangitis-an infection in the bile ducts. That’s a medical emergency. Antibiotics are needed fast.

- Find a specialist: Patients treated at dedicated PSC centers report 85% better symptom control than those seeing general hepatologists. Don’t settle for a general liver clinic.

It’s exhausting. Fatigue doesn’t go away. Itchiness lingers. You’ll feel like no one understands. That’s why patient communities matter. Online groups like PSC Partners and Reddit’s r/liverdisease are lifelines. You’re not alone. Thousands are going through the same thing.

Where Do We Go From Here?

PSC research funding is tiny. The NIH spent $8.2 million on PSC in 2022. For NAFLD, it spent $142 million. That’s not fair. But change is coming. With new drugs in trials, better imaging, and global patient registries, we’re finally moving beyond symptom management.

The goal isn’t just to delay transplant. It’s to stop the disease before it starts. To find the trigger. To block the immune attack. To give people with PSC a future without a new liver.

Right now, that future is still uncertain. But it’s no longer a dream. It’s a possibility. And for the first time, patients are part of the research-not just subjects, but partners.

Is primary sclerosing cholangitis the same as primary biliary cholangitis?

No. PSC and PBC are different diseases. PSC affects both large and small bile ducts inside and outside the liver, while PBC mainly attacks the small ducts inside the liver. PBC is strongly linked to anti-mitochondrial antibodies (found in 95% of cases), while PSC is not. PSC is more common in men and often linked to ulcerative colitis; PBC is more common in women and rarely linked to bowel disease. They require different monitoring and treatment approaches.

Can you live a normal life with PSC?

Yes-but with adjustments. Many people with PSC work, raise families, and travel. But fatigue and itching can be debilitating. You’ll need regular checkups, vitamin supplements, and possibly colonoscopies. Avoid alcohol. Maintain a healthy weight. Find a specialist who knows PSC. With good care, many live 20+ years without needing a transplant. The key is early diagnosis and consistent monitoring.

Does PSC run in families?

Not directly, but genetics play a role. If you have a close relative with PSC or ulcerative colitis, your risk is higher. The HLA-B*08:01 gene variant increases risk more than two-fold. But having the gene doesn’t mean you’ll get PSC. Environmental triggers-like gut bacteria or infections-are needed to start the disease. Most people with PSC have no family history at all.

Why does PSC cause itching?

Bile acids build up in the blood when ducts are blocked. These acids stimulate nerve endings in the skin, causing intense itching-often worse at night. It’s not just skin deep; many patients say it feels like it’s coming from inside their bones. Antihistamines rarely help. Effective treatments include rifampicin, naltrexone, and colesevelam, which bind bile acids or block the itch signal in the brain.

Is there a cure for PSC?

Currently, the only cure is a liver transplant. No medication has been proven to reverse or stop PSC long-term. But new drugs in phase 3 trials-like obeticholic acid and cilofexor-are showing promise in slowing disease progression. If these work, they could delay or even prevent the need for transplant in many patients. Research is accelerating, and the next five years may bring the first disease-modifying treatments for PSC.

What to Do Next

If you’ve been diagnosed with PSC, find a center that specializes in it. Ask for an MRCP if you haven’t had one. Get your vitamin levels checked. Schedule your colonoscopy if you have ulcerative colitis. Join a patient registry. Talk to others. Don’t accept "there’s nothing we can do" as an answer. There’s more being done now than ever before.

If you’re still undiagnosed but have chronic fatigue, unexplained itching, or ulcerative colitis-ask your doctor about PSC. Don’t wait. Early detection doesn’t cure it, but it gives you time. Time to learn. Time to prepare. Time to be part of the solution.

15 Comments

January 29, 2026 James Dwyer

It’s terrifying how little awareness there is about PSC. I’ve had three doctors tell me it was just "stress" before someone finally ordered an MRCP. Took three years. If this post saves even one person from that nightmare, it’s worth it.

January 31, 2026 jonathan soba

Let’s be real-the whole UDCA debacle is a perfect example of how medical consensus can be wrong for decades. They prescribed it because it "made sense," not because it worked. Now we’re stuck with a generation of patients who were misled. The system doesn’t learn; it just rebrands mistakes as "updates."

And don’t get me started on how underfunded PSC research is. $8.2 million? For a disease that kills people slowly and painfully? We spend more on dog food research.

January 31, 2026 Kathy Scaman

I’ve been living with this for 8 years. The itching? Yeah. It’s not just skin deep. I’ve tried everything-cold showers, oatmeal baths, even sleeping with ice packs on my arms. Nothing beats naltrexone for me, but it’s expensive and the side effects are rough. Still, I’d take the dizziness over the itch any day.

Also, yes-find a specialist. I switched from a general hepatologist to a PSC center last year and my ALP dropped 40%. It’s not magic, it’s just expertise.

February 1, 2026 Anna Lou Chen

Let’s deconstruct the epistemological crisis at the heart of PSC diagnostics. The biomedical paradigm, rooted in reductionist biomarkers, fails catastrophically here-because PSC is not a disease of isolated organs, but a systemic rupture in the gut-liver axis.

When the intestinal barrier becomes permeable, endotoxins translocate, triggering a TLR4-mediated autoimmune cascade that targets cholangiocytes. This is not mere "autoimmunity"-it’s a failure of mucosal-immune tolerance, a metaphysical betrayal of homeostasis.

And yet, we still rely on MRCP, a mere anatomical snapshot, while ignoring the proteomic, metagenomic, and neuro-immunological signatures that might hold the key. We’re diagnosing shadows while ignoring the light that casts them.

February 2, 2026 Lance Long

You’re not alone. I know what it’s like to feel like your body is betraying you. The fatigue? The itch? The loneliness of watching everyone else live while you’re just trying to get through the day.

But here’s what I’ve learned: small wins matter. Taking your vitamins. Getting that colonoscopy. Talking to someone who gets it. Joining a registry. These aren’t just "tasks"-they’re acts of rebellion against a disease that wants you to give up.

You’re not just surviving. You’re fighting. And that counts.

February 2, 2026 Timothy Davis

Actually, the 1.5% annual cholangiocarcinoma risk is misleading. That’s cumulative over time. In the first 10 years, it’s closer to 0.5%. And CA19-9 is useless in PSC-it’s elevated in 70% of patients without cancer. Most centers now use MRI-DWI, not CA19-9, for surveillance.

Also, the "20% recurrence after transplant" stat? That’s outdated. Recent studies show recurrence rates are closer to 8-12% at 10 years, and even then, it’s slow. Don’t let fear-mongering scare you off transplant-it’s still the best option.

February 3, 2026 fiona vaz

For anyone newly diagnosed: get your vitamins checked every 3 months. Seriously. I didn’t realize how low my D and E were until I started supplementing. My energy improved in weeks. And if you have UC, don’t skip colonoscopies. I caught a dysplastic lesion early because I stayed on schedule. It was removed. I’m still here.

February 4, 2026 Sue Latham

Ugh, I hate when people act like PSC is "just" a liver thing. It’s not. It’s a whole life overhaul. You have to become your own advocate. Your doctor doesn’t care as much as you do. And no, you can’t just "drink more water" and fix it.

Also, if you’re still on high-dose UDCA? Stop. Now. Your doctor might be stuck in 2015. You deserve better.

February 4, 2026 Linda O'neil

Just wanted to say: I’m 42, diagnosed 5 years ago, and I just went on a 3-week road trip across the Rockies. I packed my vitamins, my meds, and my patience. I didn’t feel great every day, but I was alive out there. PSC doesn’t get to cancel your life. It just makes you better at living it.

February 6, 2026 Bryan Fracchia

There’s something beautiful about how PSC forces you to slow down. To pay attention. To listen to your body in a way most people never learn. It’s not a gift, but it’s a teacher.

I used to think healing meant curing. Now I know it means learning to carry the weight without letting it crush you. The science is catching up. But the real progress? That’s happening in quiet kitchens, in late-night Reddit threads, in people choosing to keep going-even when no one’s watching.

February 6, 2026 Lexi Karuzis

Wait-so you’re telling me the government knows about this, and they’re STILL not funding it? And the pharmaceutical companies? They’re not interested because it’s "too rare"? That’s not a coincidence. This is deliberate. They want us to die slowly so they can sell us liver transplants. It’s a profit-driven genocide.

And don’t trust the "new drugs." They’re just testing them on us. You think they care if you live? They care if you pay for the next trial.

February 7, 2026 Colin Pierce

One thing no one talks about: the mental toll of being "invisible." You look fine. You can still work. So people say, "You don’t look sick." But inside? You’re exhausted. The itch is screaming. Your liver is dying.

It’s okay to say you’re not okay. You don’t have to be brave all the time. Just breathe. You’re doing better than you think.

February 7, 2026 Rose Palmer

As a clinical nurse specialist in hepatology, I’ve seen the transformation in PSC care over the past decade. The shift from reactive to proactive management-early MRCP screening in UC patients, routine vitamin monitoring, and the emergence of targeted therapies-is nothing short of revolutionary.

Patients who engage with specialized centers experience significantly improved outcomes. The data is clear. Please, do not settle for generic care. Demand expertise. Your future self will thank you.

February 9, 2026 Mindee Coulter

Just got my MRCP results. Strictures. Confirmed. First time I’ve cried in years. But I’m not done. I’m joining the registry tomorrow. And I’m telling my doctor I want to be on the OCA trial. This isn’t the end. It’s the start of me fighting back.

February 10, 2026 Brittany Fiddes

Of course the Americans are obsessed with transplants and trials. Over there, everything’s a product. Here in the UK, we’ve got the NHS. We don’t have access to these fancy new drugs until they’re proven. But we’ve got something better: patience. And we don’t let corporations dictate our health. You think your "hopeful" drugs are going to fix anything? We’ve been waiting decades. We’ll wait longer.

Write a comment